PLEASE NOTE: JAPWANCAP WAS NEVER ACCEPTED AS A LEGITIMATE ORGANIZATION BY ANY GOVERNMENT. THE CERTIFICATES CANNOT BE REDEEMED. THEY ARE ONLY WORTH WHAT A COLLECTOR WOULD PAY FOR THE CERTIFICATES. A CERTIFICATE AND ALL DOCUMENTATION THAT GOES WITH IT WILL PROBABLY BE WORTH AROUND $50 ON EBAY, BUT THAT IS ABOUT ALL.

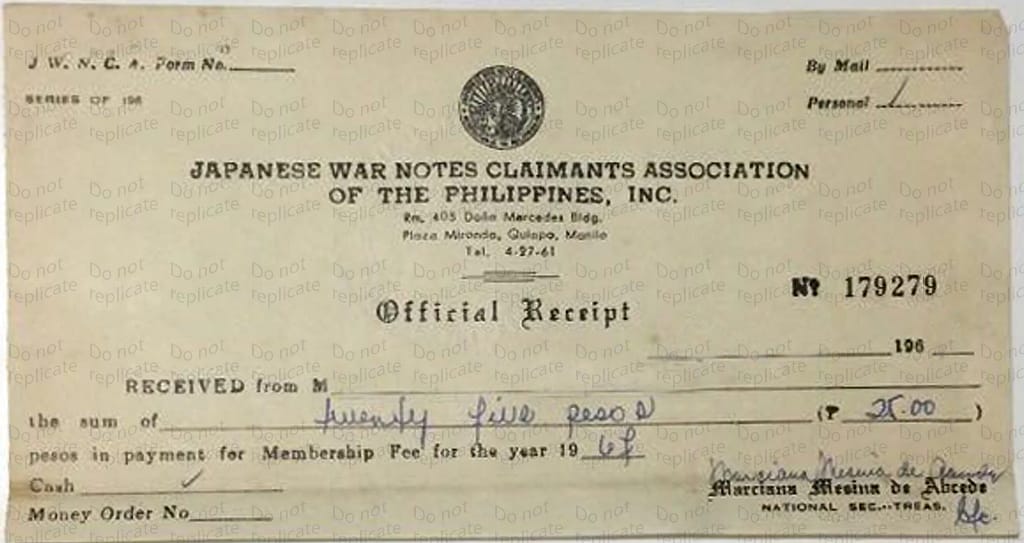

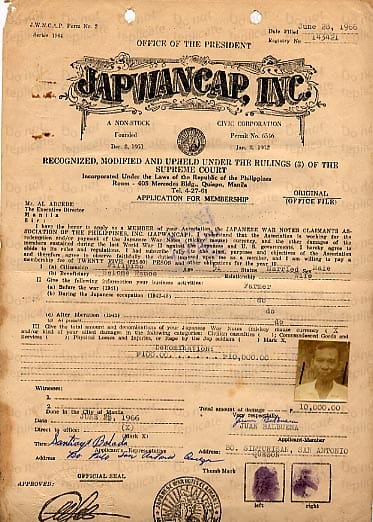

After World War II most Filipinos held large quantities of the worthless Japanese Invasion Money that was issued by the Japanese Occupation Forces. The JAPANESE WAR NOTES CLAIMANTS ASSOCIATION OF THE PHILIPPINES, INC. (JAPWANCAP) was formed on January 8, 1953 by Al Alcede, with the promise that the worthless currency would be redeemed with spendable currency. People would join the organization and turn their Invasion Money over to the organization and then would be billed storage on the money and/or charged a fee for the issuance of a certificate of registration. The notes were haphazardly counterstamped by one of at least 8 known counterstamps, using various ink supplies. These counterstamps were applied to either the front or the back of the notes.

An excerpt from the MPC GRAM – Number 856 published Sunday February 23, 2003 explaining why JAPWANCAP had no legitimacy

The principles of international law recognize the right of an occupying force to determine what medium will serve as legal tender in the area under occupation. Through the course of history, different occupying forces have chosen to deal with the issue in many different ways. Japanese Invasion Money (JIM) and Allied Military Currency are two examples of currency declared as legal tender by the occupying powers and imposed on the local population. Not all occupying forces imposed a new currency in the territory they occupied. While the Germans issued Reichskreditkassenschein marks in occupied eastern Europe while they allowed the Bank of France to continue to circulate its notes in Vichy and occupied France. More recently, Israel allowed the Jordanian dinar to circulate in the occupied West Bank until 1987. The use of occupation currency leads to the question of “What is the status of debts paid using occupation currency after the occupation ceases?” The post-war treatment of debts paid in Japanese Military Pesos is interesting and somewhat surprising.

The Japanese Military Administration in the Philippines declared the JIM Peso notes as legal tender in the Philippines by a Military Proclamation dated January 3, 1942. (I have been unable to locate a copy of the Proclamation. If anyone has access to one, please contact me at mufelika@itol.com . The information that follows regarding the Proclamation is taken from the post-war decisions of the Philippine Supreme Court that will be discussed below.) The Proclamation of January 3 imposed severe penalties for refusing to accept JIM. Although the Proclamation of January 3 did not invalidate the pre-occupation currency of the Philippine Commonwealth, this currency nonetheless disappeared from circulation.

Despite the occupation and the turmoil of the war, commercial life in the Philippines continued under Japanese rule. The occupation did not terminate the civil and contractual obligations between citizens. Rent was still paid, contracts were made, and debts were due. The disappearance of Commonwealth currency and the penalties for using Guerrilla currency compelled many Filipinos to use JIM in everyday commerce. Court records indicate the JIM peso circulated at par with the pre-occupation Commonwealth peso and at the pre-war exchange of 2 pesos to the US dollar until the middle of 1943. The JIM peso began a quick devaluation as the tide of the war turned against Japan.

After liberation of the Philippines by MacArthur’s forces, a question arose as to the status of the contracts and other settlements made during the occupation. In a letter to the Secretary of the Treasury dated October 25, 1945, President Truman directed that the issue be looked into. The United States High Commissioner for the Philippines Paul V. McNutt, in consultation with the Treasury and Philippine and American business leaders, developed a plan to validate certain payments made in JIM.

The Philippine Congress rejected the proposal. Instead, in February 1946 the Philippine Congress passed an act that validated all transactions made in JIM. The Act was subsequently signed by Philippine President Sergio Osmena.

Under the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1936 which gave the Philippines commonwealth status and the Philippine Constitution, all acts of the Philippine Congress that affected currency were subject to approval by the President of the Unite States. In a statement dated February 7, 1946, President Truman rejected the act of the Philippine Congress that validated payments made in JIM. (Incredibly, the Truman Statement refers to the Japanese pesos as ‘mickey mouse’ money.) The issue remained unsettled when the Philippines attained independence on July 4, 1946.

In a series of cases beginning in 1946, the Philippine Supreme Court upheld the validity of the payment of debts in JIM that were incurred both before and during the occupation. The Court based its decisions on the long-recognized principle of international law that an occupying force has the authority to declare legal tender. In support of this conclusion, the Court pointed to the Combined Directives of the Combined Chiefs of Staff of the Supreme Allied Commander dated June 24, 1943, April 28, 1943 and June 27, 1947 which authorized the use of yellow seal dollars and British Military Authority notes in Sicily, AMC marks and yellow seal dollars in Germany, and AMC schillings in Austria. (If anyone has access to the Combined Directives, please contact me.) The Court also based their decisions on the fact that it was impossible to make payment in any currency other than JIM since the Commonwealth currency had disappeared from circulation. Interestingly, the Court does not mention the circulation of guerrilla currency, a fact of which they must have been aware.

In the case of Rosario v. Sandico (G.R. No. L-867) the Philippine Supreme Court made the following observations:

If the Japanese war notes became depressed and valueless, it was because the war was prolonged and lost by the Japanese contrary to their expectation of winning the war in a short time, and not because they issued purposely a depressed and valueless currency as legal tender. If their expectations had been realized no question as to the validity of the Japanese military notes as legal tender would have come up.

Besides, the Court of Appeals could not have rendered a judgment sentencing the plaintiffs to pay this obligation or to pay money or the sum of P3,944.20 to Sandico in a currency other than the Japanese war notes; because such judgment would have been contrary to the Proclamation of January 3, 1942 and notification of February 23, 1942 issued by the Japanese Military Administration . . .

And because, although the circulation of the Commonwealth currency was not then prohibited legally because of the Proclamation of January 10, 1942, they had already disappeared from circulation at that time, as above stated; and for the Court of Appeals to have ordered in the judgment that the sum of P3,944.20 shall be paid . . . in Commonwealth legal currency, would have been tantamount to order the execution of a thing which was impossible to do and which might be possible to perform in the future, inasmuch as there was no assurance that the Commonwealth of the Philippines shall be restored, and such kind of currency recognized as legal tender by the government then established by the Japanese or to be established in the future.

Jim Donwey

NOTE: Here is the text of Truman’s letter to the Secretary of the Treasury, and here is the text of Truman’s statement disapproving the act of the Philippine Congress.

Rosario v. Sandico can be found here.

Another interesting read about this money is here.

U.S. Army Signal Corps photograph, Gift of Donald E. Mittelstaedt, from the collection of the National WWII Museum

JAPWANCAP membership application